Talk about Bengali and the image of a “Bhadralok/Bhadramohila” comes up in front of our eyes – intellectual, argumentative, agitational, cultured – well read with taste of art and music, sipping tea and smoking cigarette. S/He would typically be an employee working either in a Govt sector or in a Private sector. But Bengali and Entrepreneur? Seems like an oxymoron… a total contradiction – Right?

But this was not like this always…….

Let’s take a walk down memory lane and see how things were and how did they change.

Remember the saying “Banijye Basate Lakshmi” i.e. Lakshmi or Wealth is in Commerce. Ancient Bengal believed in this. One of the earliest sea -farers of India were from Bengal. Extensive writings are available on the trade links that ancient Bengali traders had established with other parts of coastal India and also with countries in South East Asia, Sri Lanka and even West Asia. Initial commerce focused on agri-produce (Paddy and Sugarcane) gradually diversifying into value added materials like Textiles (Muslin). Tamralipti followed by Samandar/Sattigaon were ancient Bengal’s (and India’s) one of the largest ports. Lot of references have been found of trade voyages being sent to islands like Sumatra, Java, Bali, Sri Lanka from these ports including references of settlement of people from Bengal to these places ( this is corroborated by many similarities in cultural practices between Bengal and these places as well as by scientific anthropological studies).

Literary references of iconic Bengali traders like Chand Saudagar, Bihari Datta from this ancient period have been found.

This continued till the Islamic invasion of Bengal in early 13th century. With Islamic invasion, there was a total shake up of Bengal’s social and cultural fabric. Since the major focus of Turks/Afghans were on land route-based trade, gradually the focus on sea trade started diminishing and the political/military control of the seas were taken over first by Arabs and then by the Europeans. So, while the sea trade from Bengal still continued, Bengalis were forced to sell/supply via these Arab/European traders who were backed by their respective kingdoms.

The death knell to the trade was sounded post the battle of Plassey when East India Company became the de-facto ruler of Bengal Bihar and Odisha. British forced Bengal to become a supplier of raw materials (at a very low price) and started dumping finished goods produced in Britain by taking advantage of industrial revolution. Repression, physical torture and blood sucking taxation system completely crippled the thriving cottage industry of Bengal. When the British took over Bengal, Muslin cloth was world famous and used to go to far off places like Bagdad, Rome, China and was highly valued for its intricate design and fine works. Within a few years, British made sure that this textile industry is completely destroyed in Bengal and from a huge net surplus of textile production, Bengal became an importer of textiles produced in Manchester.

From the time of the battle of Plassey till late nineteenth century, there is not much of entrepreneurial activity worth talking about in Bengal as this was the time when British was ruthlessly suppressing all economic activity of Indians, making India the supplier of cheap raw materials and forcing it to consume value added goods produced in large factories.

Then gradually there started a new generation of Bengalis educated in British education system, many of them went abroad to complete their higher studies and hence got exposed to the modern industrial economy of Europe. This was the onset of “Bengal Renaissance” wherein educated Bengali youth started developing a sense of nationalism and a section of them wanted to contribute to the country by starting indigenous industrial units.

The list of these luminaries is quite long – Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray of Bengal Chemicals & Pharmaceuticals, Sir R.N. Mookerjee / Sir Biren Mookerjee of Martin Burn, K.C. Das of Calcutta Chemicals, S.M. Bose of Bengal Waterproof (Duckback), Gourmohan Datta of G.D. Pharmaceuticals (Boroline), Subir Sen of Sen Raleigh and many others. These enlightened nationalist industrialists put a solid foundation of indigenous industries, tapped whatever limited capital was available and provided employment to a large number of Bengali youths.

When India became independent in 1947, West Bengal was the most industrialised state in India in all parameters – be it total industrial output or number of factories or number of workers employed. However, the downward slide was quite fast. By 1958-59 Bengal’s share in India’s total industrial output had come down to 22% (still no 2 in India behind Maharashtra). Subsequently it was a steady run towards the bottom – 10.9% in 1975-76 to 6% in 1990-91 and a meagre 3.97% in 2016-17!

Even in terms of number of factories, West Bengal was the undisputed no 1 in India with 1493 factories in 1950-51. By 1960-61, Bengal had lost the 1st spot to Maharashtra who had become no 1 with 1,724 factories (from around 1,000 in 1951). And by 2016-17, W.B. has slipped to no 7 position with 9587 factories way behind No 1 T.N with 37220 factories, Maharashtra no 2 with 27010 and Gujarat no 3 with 25966 factories. Even states like A.P (16246), U.P. (15294) and Telangana (15028) are way ahead of Bengal.

All other indicators of industrialization are also showing similar downward trend for Bengal.

So, what went wrong??

The most common answer political parties (and many “intellectuals” in Bengal) give is “Centre’s step-motherly treatment”. While it is true that successive Central governments did not proactively encourage industrialization in Bengal, the major problem lies some where else. Yes, the Freight Equalisation policy promulgated by Central Govt in 1952 (remained till 1993) took away the locational advantages that states in Eastern India (mostly rich in minerals) had over their relatively mineral resource poor counterparts in Western, Southern or Northern India. But that can’t explain the flight of capital from Bengal for all existing industries as well as industries which are not so much dependent on minerals.

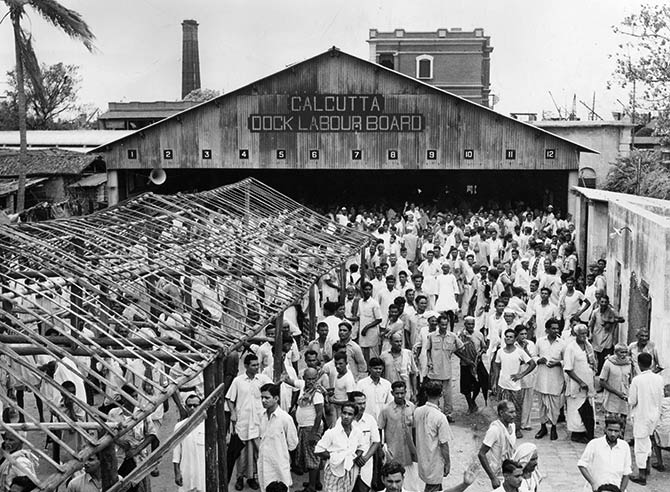

The fact is that the Communists had a lot behind this flight of capital from Bengal. They were successful in spreading this ideology even among general masses that all capitalists (which included all the industrialists) are to be hated as they are class enemies. While sporadic violence against the Management and Owners of companies had started in late fifties/early sixties itself, this reached its crescendo once the United Front govt took office in 1967 with backing of Communists. Aditya Birla was assaulted in broad day light in Calcutta and made to walk the streets in torn clothes in the city in which he grew up. This led to the Birla shifting his headquarters out of Calcutta. Two other major industrial groups of India at that time – Singhanias and Thapars also soon moved out of the city. It is rumoured that the Tatas had actually planned to shift their corporate office to Calcutta from Bombay but with growing industrial violence, they decided not to go ahead with it. The Naxal violence of late ‘60s and early ‘70s only hastened this exodus of corporates from Calcutta and infact by the time the Left Front govt took office in 1977 with full majority, only a handful of corporates were still having their factory/corporate office in Bengal. These handful like Philips, Bata, ICI, Shaw Wallace, Ispat Industries et al also left Bengal by early to mid- nineties turning Bengal into a virtual graveyard for corporates. During all these years, all those industries that were built by nationalist Bengalis during early twentieth century, also one by one died – most of them having a history of labour unrest and industrial violence behind their demise. There were a few indomitable Bengali entrepreneurs who set up new industries in the state post-independence and they also met the same fate.

Obviously the Central govt also contributed its own bit during all these years by being stingy in giving licence to any one wanting to set up unit in Bengal – this is the story till early nineties as Licence Raj was in operation in the country and the Central Govt could decide who will operate which industry, where and produce how much. Further there were many Engineering companies in Bengal dependent on orders from Railways (the likes of Braithwate, Jessop etc) which the Central govt deliberately withheld/reduced, to settle score with the Left Front govt in Bengal.

After Jyoti Basu demitted office in 2000, Buddhadev Bhattacharya realized the gravity of the un-employment problem and the time bomb on which his govt was sitting on. So, he tried hard to bring investments to the state and partially succeeded but by that time, Bengal had got its new more hardened “Left” in the form of Mamata Banerjee. Her agitation in Singur drove the Tatas away (and alongwith them many other entrepreneurs who were thinking of investing in a changed Bengal), led to the fall of 34 year long Left Front regime but started another round of sad innings in matters of industry turning Bengal into a market for consumption with hardly any industrial production worth talking about.

Today, vast majority of educated and professionally qualified Bengalis are working in corporate sector in places like Mumbai, Delhi, Gurgaon, Noida, Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad, Ahmedabad, Pune and in so many other places all over India. But talk to them about going back to Bengal and most of them would say no. For them, Bengal is only a place to go once/twice a year for a few days to meet their family members who are still there (mostly parents or old relatives), enjoy good food and talk about culture and nostalgia. Many of these Bengalis are also investing in start ups or small businesses but again hardly any of them would dare to that in Bengal.

So the wait for an industrial and entrepreneurial revival in Bengal only gets longer……..probably till the time the next real “Poribortan” takes place in politics of the state.

IMAGE: Starting in the 1960s, labour disputes and lock-outs in many companies lasted more than a year, marking their decline. Photograph: Keystone/Getty Images (Picture source: rediff.com)