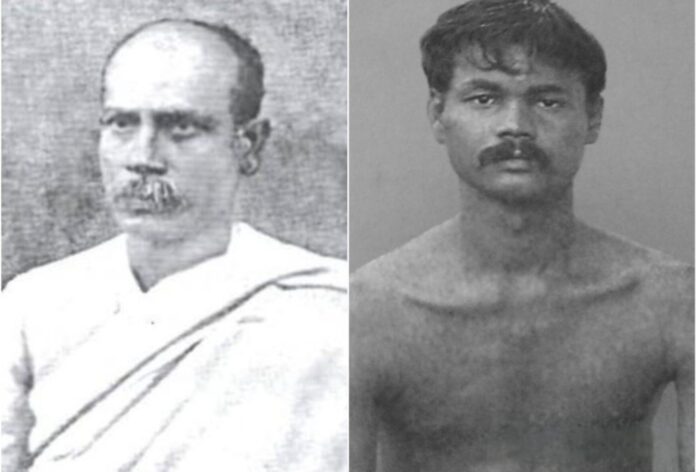

Pulin Behari Das stands among that rare breed of revolutionaries who could instil fear in the British Raj merely by the mention of their name. Founder of the Dhaka Anushilan Samiti, he was not a distant ideologue but a hands on architect of armed resistance, a man who turned physical strength, weapons and discipline into instruments of national revolt. The colonial establishment, usually contemptuous of “native” bravado, regarded him as a genuine threat, a living challenge to imperial authority in eastern Bengal. Among Bengali Hindus, his impact still looms as an unquiet memory of what a militant, organized and weapon trained community could mean in the face of foreign power.

Born on January 28, 1877, Pulin entered a Bengal dominated by clerks, lawyers and literary men, where the pen was praised but the sword was half forgotten. From a tender age, however, he gravitated toward the world of arms. Lathi, sword, stick fighting and physical exercise fascinated him far more than the safe comforts of the classroom. Over time, he moulded himself into an excellent fighter, not as a mere sportsman but as someone consciously preparing for struggle. In an era when the British preferred to see Bengalis as fragile and bookish, Pulin’s life became a rejection of that stereotype. He built his body like a fortress and his will like a weapon, announcing by sheer presence that the age of the unarmed Hindu was over.

The Dhaka Anushilan Samiti, which he founded and led, was the organizational expression of this philosophy. Outwardly, it could present itself as a club focused on physical culture and character building. In reality, it was a laboratory of rebellion, a place where young Hindu men were trained to think, move and fight like disciplined soldiers. Rigorous drills, silent obedience, loyalty to the motherland and familiarity with weapons forged them into a parallel force beneath the surface of colonial order. Under Pulin’s command, Dhaka became more than a provincial town. It turned into the nerve centre of a clandestine martial awakening, a space where weakness was despised and courage, even at the cost of life, was honoured.

Pulin was not a neutral nationalist. He was a die hard Hindu, proud of his identity and unprepared to dilute it for the sake of imperial comfort or fashionable compromise. Throughout his life he remained at daggers drawn with both the British government and Islamist currents that, in his experience, were often aligned against Hindu interests in eastern Bengal. He saw no virtue in passivity when his community faced both foreign domination and hostile communal aggression. This conviction transformed his followers into shields and swords for Hindu society. They were expected not only to dream of freedom but to defend neighbourhoods, rally youth and demonstrate that Hindus could no longer be pushed, humiliated or massacred without resistance.

The British response was predictable and ruthless. They watched Dhaka Anushilan with growing alarm, tracing its networks, infiltrating its ranks, building cases to justify crushing it. Eventually the empire struck hard. Pulin was arrested and sentenced to transportation, exiled to the dreaded Andaman Cellular Jail, a place designed to break the hardest of men. The Cellular Jail was a fortress of isolation, torture and forced labour, where prisoners were worked, whipped and starved into submission. Pulin spent years in that grim environment, cut off from the land he was fighting for, surrounded by cruelty and despair. Yet the jail failed to break him. He remained defiant, spiritually unbowed, his mind fixed on the freedom of the motherland even when his body was chained.

That defiance inside the Andamans became part of his legend. The British could imprison him on a distant island, but they could not erase what he represented. To comrades and later generations, Pulin symbolized the idea that a Hindu revolutionary was not merely a thinker or a speaker, but someone willing to embrace suffering, hard labour and confinement without surrendering conviction. The culture of arms he had cultivated in Bengal followed him into the prison as an inner discipline, a refusal to collapse even in the face of systematic dehumanization. The empire punished him severely, yet in doing so it confirmed his stature as an enemy it truly feared.

Among Bengali Hindus, Pulin Behari Das remains an exceptional figure. Many leaders wrote, debated or negotiated, and a number of revolutionaries took to arms at different moments. But no other individual so completely immersed in the culture of weaponry has shaken the socio political and psychological landscape of Hindu Bengalis in quite the same way. He did not treat weapons as occasional tools but as a civilizational necessity for a people too long taught to be timid. The very idea that Hindu society in Bengal could organize itself around strength, training and readiness to fight owes a lasting debt to his vision and practice.

His legacy lies not only in specific actions or organizations but in the deeper message his life transmits. A community that abandons its capacity for defence and courage invites subjugation. A nation that relies solely on words before an armed oppressor dreams of freedom but does not secure it. Pulin’s journey from youthful fighter to founder of Dhaka Anushilan Samiti, from the streets of Bengal to the cells of the Andamans, demonstrates that resistance demands more than speeches and petitions. It demands bodies hardened, wills sharpened and a readiness to pay the highest personal cost.

To this day, when one looks back at the history of Bengali Hindus, Pulin Behari Das stands as a stark reminder of a different path that was once taken with full awareness and fierce pride. He was the embodiment of a Hindu Bengal that refused to be a passive spectator to its own humiliation. His name may not appear as frequently in popular narratives as some others, but within the story of armed awakening, he is a pillar. And as long as the question of strength, self defence and honour remains alive in Hindu Bengal, the figure of Pulin Behari Das will continue to rise from history as a challenge, a warning and an inspiration.