In 1964, the entire East Pakistan was rocked by violence against the minority Bengali Hindu community. Anti Bengal Hindu riot broke out across the region because a preserved piece of hair of Prophet Muhammad was allegedly stolen from Hazratbal Mosque in faraway Kashmir, in India! Khulna’s Bengali Hindu residents were the worst affected in the pogrom, following which a huge influx of fresh migration into India started. No sane person could figure out what exactly went wrong with Bengali speaking Muslims which made them attack their Hindu counterpart.

History repeated in Bangladesh in 1992. This time a 500 year old usurper structure known as Babri mosque was brought down by a Hindu mass uprising in Ayodhya, India. Reaction from the Islamist fundamentalists was very much visible in Bangladesh as whole country was swept by another fresh anti Bengali Hindu violence. The Bangladesh government was a mute spectator as the Pakistan government had been in 1964. Still nobody tried to answer the question why Bengalis are so vulnerable in a country which proudly claims to have gained freedom for Bengali language from the clutches of Pakistan.

To the average Bengali-speaking Muslim, it was the non-Muslims who were behind the attacks (or vandalism as they believed it to be) in Kashmir or Ayodhya, on what they believe to be Islamic artifacts or symbols. Being unable to vent their anger on the people who actually caused the attacks, they took it out on the innocent non-Muslims in their vicinity i.e. Bengali Hindus, their neighbors. Through this behavior, they

demonstrated that their religious solidarity is more than linguistic solidarity and that their religious identity can transcend linguistic identity as and when required.

This behavior was actually spelt out in words by none other than Sher-e-Bangla Abul Kashem Fazlul Haque, who had said (before the Partition), if there is any attack on Muslims in any province of India, then he would avenge it by attacking the Hindus of Bengal. Bipin Chandra Pal, known as the father of Indian revolutionary nationalism, had warned long ago in his essay ‘Nationalism and Politics’ that such pan-Islamism would turn out to be the ‘real danger’ in the Indian subcontinent.

Pleasant lies are more preferable than uncomfortable truths. Multiple generations never got to know about persecution of Bengali Hindus in East Pakistan and later Bangladesh in the hands of Bengali speaking Muslims, let alone understanding the nature of Islamic aggression. History of empty train compartments with blood stained clothes and broken sankha-pola arriving in Sealdah from East Pakistan have been replaced by isolated experiences of individual assistance, which are exceptions at best. The design of Islamic onslaught in the Noakhali genocide or the ‘Great Calcutta Killings’ inspired from Wahhabism, Salafism has been hidden under the carpet and carefully cherry-picked tales of exceptions have been fed. As a result, a false sense of fraternity has been imparted among Bengalis particularly of West Bengal.

This artificial sense of ‘Hindu-Muslim’ unity is the bedrock of so called Bengali Nationalism which demands realization of a ‘independent united Bengal’. What is unity between two different communities? Can language be only such a unifying parameter? To answer the first question, it is required to realize that eating ‘simui’ or ‘biryani’ by Ramesh in the house of Rafique and visiting Durga Puja ‘mandap’ by Rafique accompanied by Rajesh may be an example of mere social courtesy or anything else but unity. Unity stands for the common goal of cultural capitalism and political agenda which had no existence in Bengal either in the past or it has in the present.

The Bengali-speaking Muslim elites led by Nawab Salimullah supported Curzon’s plan of Bengal Partition and founded the Muslim League in 1906. Even Rabindranath Tagore’s ‘Rakhi Bandhan Utsab’ failed to get Muslims’ support against the anti-partition Swadeshi and Boycott movement. They refused to participate in native start ups of textile and salt because they were manufactured by Bengali Hindus.

The Bengali-speaking Muslims printed the infamous ‘Laal Istahar’ to persecute Hindus of East Bengal that led to anti Bengali Hindu pogroms in Jamalpur and Comilla in the newly created province of Eastern Bengal and Assam and triggered an exodus of Bengali Hindus to Bengal. Legendary author Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay who is mostly known as the creator of iconic ‘Debdas’ rightly pointed out in one of his speeches that Muslims of India were the least interested in domestic affairs or anti colonial struggle as their hearts had always been in Arab or Turkey. [Bartoman Hindu Musalman Samasya, 1926]

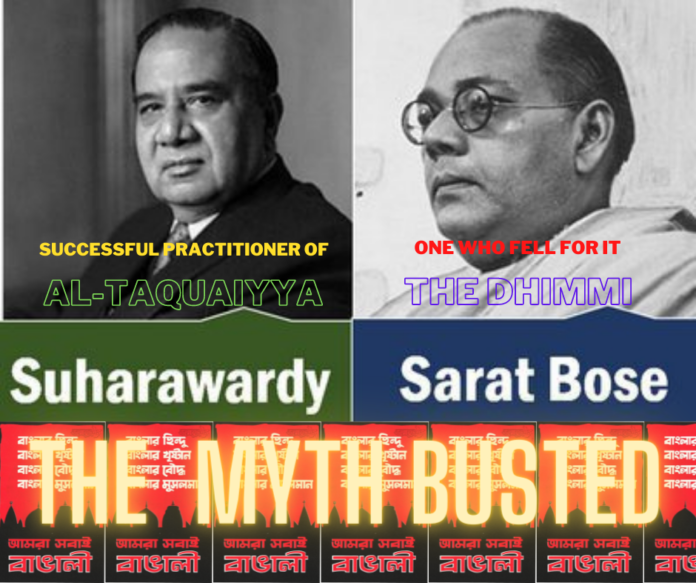

In 1940, it was the leading Bengali-speaking Muslim politician Abul Kashem Fazlul Haque, the then PM of Bengal, who in spite of not being a Muslim Leaguer at the time, spelt out the Pakistan proposal at the Muslim League convention in Lahore. The Pakistan proposal envisaged two Muslim majority states – one in western India and another in eastern India, considering the fact that in Bengal the Muslims were in a majority. Later, in 1946, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, also a Bengali-speaking Muslim politician and the then PM of Bengal cemented the idea of a singular unitary Pakistan.

In the same year, Suhrawardy along with his right hand Sheikh Mujibur Rahman became the key conspirators in the Direct Action against the Bengali Hindus in their quest for Pakistan. Language was not a factor that could unify them with the Bengali Hindus. It was only when the Bengali Hindus led by Syama Prasad Mookerjee began to campaign for a Bengali Hindu homeland, and it dawned upon Suhrawardy that western Bengal from where he belong might not get ceded to Pakistan, he floated the idea of United Bengal, citing the common language and culture of the Bengali-speaking people.

Bengali Nationalism which is said to stand on the foundations of shared Bengali language and Hindu-Muslim unity had its acid tests in the Partitions of 1905 and 1947, where it all but failed miserably. The Bengali Hindus and the Bengali-speaking Muslims had different if not outright contradictory outlook of history and divergent political and economic aspirations, which led to the failure of the utopian Bengali Nationalism. These two watershed moments upheld that Bengali identity essentially as well as exclusively belongs to Hindus only.

On 21st February 1953, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, then General Secretary of the Awami Muslim League in East Pakistan suggested to observe the day as ‘National Karbala Day’. Karbala, in present day Iraq, is famous for the battle for supremacy between the Sunni and Shia factions in the early days of Islam. In the subconscious mind of Bangladesh’s father of the nation and Bangabandhu, the language movement which culminated in the killings of the protestors and bystanders in police firing on 21st February 1952, was nothing but an internal power struggle among the two entities within Pakistan the West Pakistanis and the East Pakistanis. Language was just a matter of coincidence.

Awami League’s landslide victory in the 1970 elections meant that the power centre would shift from West Pakistan to East Pakistan, which the former was reluctant to let go of. As the talks failed, the situation quickly escalated into a civil war between the two wings of Pakistan, until India officially intervened and liberated Bangladesh from Pakistan. The Six Point Demand of 1966 that pretty much served as the election manifesto in 1970, was drafted by veteran Awami League leader Abul Mansur Ahmed on behalf of Mujib. The demands included administrative reform in line with Lahore Proposal of 1940, limiting federal government’s authority, fiscal & monetary policy reform, external trading and formation of regional armed forces. There was not a single demand related to language. Indeed, Bengali was the official language of Pakistan at the time since 1956; it was used for all official purposes including bank notes, coins, postage stamps etc.

In spite of the above nature of Ekushey and Muktijuddho, the Bengali-speaking Muslim leadership had used Bengali Hindu population as pawns when it was necessary to establish demographic majority of Bengali-speakers to Urdu-speakers where be it in demanding Bengali as the official language or demanding autonomy of East Pakistan over West Pakistan. However, in doing so, the linguistic identity never transcended the religious identity. The 1956 constitution of Pakistan not only made Bengali as the official language it also made Islam the state religion. In the case of Bangladesh, if the linguistic identity had ever eclipsed the religious identity, it was only temporary. The reversal started in 1975 and finally completed in 1988, when Islam was declared the state religion.